22 Dec 2025

- 15 Comments

When your heart valve doesn’t open or close right, it doesn’t just cause a murmur-it changes your life. Imagine trying to climb stairs and suddenly feeling like you’re breathing through a straw. Or waking up at night gasping for air, even though you’re not sick. These aren’t normal signs of aging. They’re warning signs your heart valves are failing.

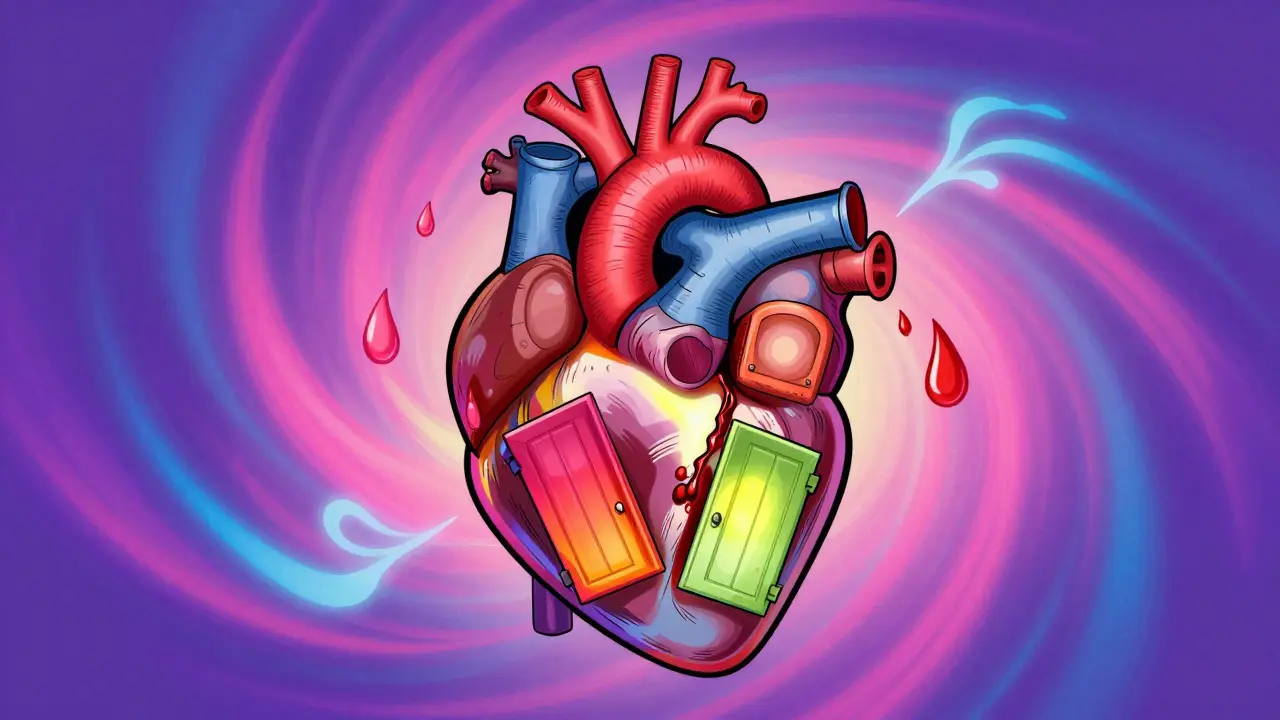

What Happens When Heart Valves Don’t Work

Your heart has four valves: aortic, mitral, tricuspid, and pulmonary. They’re like one-way doors. Each opens to let blood flow forward, then snaps shut to stop it from leaking back. When these doors get stiff or don’t close tight, problems start. Stenosis means the valve opening is narrowed. Blood can’t flow through easily. The heart has to pump harder, like squeezing a kinked garden hose. Over time, the muscle thickens, tires out, and starts to fail. Regurgitation (or insufficiency) is the opposite. The valve doesn’t seal. Blood leaks backward. Your heart ends up pumping the same blood over and over, wasting energy. It’s like trying to fill a bucket with a hole in the bottom. The most common serious types are aortic stenosis and mitral regurgitation. Aortic stenosis affects about 2% of people over 65. In most cases, it’s caused by calcium buildup on the valve leaflets-like rust forming on a metal door hinge. Mitral regurgitation often comes from a stretched or torn valve leaflet, or from the heart chamber itself enlarging and pulling the valve apart.Stenosis vs. Regurgitation: How They Feel Different

People often confuse the two because both cause fatigue and shortness of breath. But the patterns are different. With aortic stenosis, symptoms usually show up together: chest pain when you exert yourself (angina), dizziness or fainting (syncope), and trouble breathing even at rest. About half of patients with severe aortic stenosis have at least one of these. Left untreated, only half survive five years. With mitral regurgitation, the symptoms creep in slowly. You might feel tired all the time, even if you’re not doing much. Palpitations-like your heart skipping or fluttering-are common. You might notice swelling in your legs or abdomen. Unlike stenosis, symptoms often don’t appear until the heart is already struggling. Mitral stenosis, often caused by old rheumatic fever, is rarer now in the U.S. but still common in developing countries. It causes fluid to back up into the lungs, leading to nighttime coughing, wheezing, and needing extra pillows to sleep.How Doctors Know It’s Serious

Not every leak or stiff valve needs surgery. Doctors use echocardiograms to measure the damage. For aortic stenosis, severe means:- Valve area smaller than 1.0 cm²

- Peak blood speed over 4.0 meters per second

- Pressure difference across the valve over 40 mmHg

When Surgery Becomes Necessary

The good news? Surgery saves lives. The better news? You don’t always need open-heart surgery anymore. For aortic stenosis, the standard used to be open-heart valve replacement. Now, TAVR (transcatheter aortic valve replacement) is the first choice for most patients over 65, especially if they have other health issues. TAVR uses a catheter threaded through the groin to place a new valve inside the old one. Recovery is weeks, not months. Studies show TAVR cuts death risk by 12.6% compared to open surgery in high-risk patients. For younger, healthier patients under 70, surgical replacement still lasts longer. Mechanical valves last decades but require lifelong blood thinners. Bioprosthetic valves (made from animal tissue) don’t need blood thinners but wear out in 15-20 years. Newer versions may last longer. For mitral regurgitation, repair is better than replacement if possible. Surgeons can reshape the valve, patch holes, or tighten the ring around it. The MitraClip is a device inserted through the leg that grabs the leaking leaflets and clips them together. It’s not for everyone-but for those with functional regurgitation (caused by heart enlargement), it cuts death risk by 32% compared to meds alone. For mitral stenosis, balloon valvuloplasty is often the first step. A balloon is inflated inside the valve to stretch it open. It’s quick, low-risk, and gives quick relief-though the valve may narrow again over time.What Recovery Really Looks Like

People think valve surgery means months of bed rest. That’s not true anymore. After TAVR, most patients are walking the day after. Many report feeling like themselves within 30 days. One patient on a heart forum said, “I went from struggling to walk to the mailbox to hiking three miles in two months.” Open-heart surgery takes longer. Sternotomy (cutting through the breastbone) causes pain for 6-8 weeks. Lifting grandchildren, carrying groceries, even hugging your kids can feel impossible. But the payoff is worth it. Studies show 92% of TAVR patients report improved energy levels. For surgical patients, 90% survive 10 years after mitral valve repair. The biggest challenge isn’t the surgery-it’s the wait. Nearly 30% of patients say doctors dismissed their symptoms until they were near collapse. If you’re tired all the time, short of breath, or getting dizzy, don’t let anyone tell you it’s just age. Get an echocardiogram.

What’s Next for Valve Treatment

The field is moving fast. In 2023, the FDA approved the Evoque system for tricuspid valve repair-the first transcatheter option for that valve. The Cardioband system is being tested to shrink leaky mitral valves without cutting the heart open. The Harpoon system, still in trials, lets surgeons precisely reattach valve leaflets using a tiny anchor. By 2030, experts predict 80% of valve procedures will be done through catheters, not open surgery. Even younger patients, previously told to wait, may be candidates for TAVR as devices get more durable. The biggest concern now is long-term valve durability. Bioprosthetic valves still wear out. About 1 in 5 fail by 15 years. But new tissue treatments, like those using stem cells or synthetic scaffolds, could extend valve life to 25+ years.What You Should Do Now

If you’re over 65 and have unexplained fatigue, shortness of breath, or chest discomfort, ask your doctor for an echocardiogram. Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse. The window to act before heart damage becomes permanent is narrow. If you’ve been told you have a valve leak or narrowing:- Get a second opinion from a valve specialist, not just a general cardiologist.

- Ask if you’re a candidate for TAVR or MitraClip.

- Find a center that does at least 150 valve procedures a year-experience matters.

- Don’t ignore symptoms just because you’re “too old” for surgery. Age isn’t a barrier anymore.

Christine Détraz

December 24, 2025I never realized how much my grandma’s fatigue wasn’t just ‘getting old’-she had severe aortic stenosis and no one caught it until she collapsed. TAVR saved her life. Now she’s gardening again at 82. Don’t brush off symptoms. Get checked.

Also, why do so many doctors still act like surgery is a last resort? It’s not. It’s a tool. And we’re way past the ‘wait until you’re dying’ model.

CHETAN MANDLECHA

December 25, 2025As someone from India, I’ve seen rheumatic heart disease still wreck lives here. Mitral stenosis isn’t rare-it’s just ignored because healthcare access is uneven. We need cheap screening programs, not just fancy catheters in the West.

Jillian Angus

December 25, 2025My mom had mitral regurgitation. They told her to wait. She waited five years. By then her heart was stretched. Surgery fixed it but she still gets tired. Don’t wait. Get the echo. Even if you feel ‘fine’.

Ajay Sangani

December 26, 2025its funny how we treat the heart like a car engine but forget its alive. valves dont rust like metal they calcify like bone. and we fix them with metal and pig tissue. we’re patching biology with engineering. maybe we should be asking why this happens instead of just fixing it after the fact.

Gray Dedoiko

December 27, 2025My uncle had TAVR last year. He was on oxygen before. Now he’s teaching his grandkids to ride bikes. It’s wild how fast recovery can be when you’re not stuck in the old-school mindset. Doctors need to stop assuming age = risk. Sometimes age = wisdom.

Aurora Daisy

December 27, 2025Oh great. Another American miracle cure. Meanwhile, in the UK, we’re still waiting six months for an echo because the NHS is broke. TAVR? Great. But only if you’re rich or lucky enough to live near a big city. This isn’t medicine-it’s luxury healthcare with a heart-shaped sticker.

Paula Villete

December 27, 2025So… we’re replacing heart valves with pig parts and calling it progress? Cute. I mean, it works. But imagine if we treated other organs like this. ‘Oh your liver’s tired? Here’s a cow kidney.’

Also, typo: ‘MitraClip’ not ‘MitraClip’. Just saying. But seriously-this tech is incredible. Why aren’t we funding research to make valves last 40 years instead of 15? We can send rockets to Mars. Why not fix biology properly?

Georgia Brach

December 27, 2025Let’s be honest-this whole narrative is industry-driven. TAVR is profitable. Bioprosthetic valves? High-margin disposables. The real question isn’t ‘when should you have surgery?’ It’s ‘who profits from your heart failing?’

And yes, I’ve read the studies. They’re funded by Medtronic, Abbott, Edwards Lifesciences. Of course they say TAVR is better. They make it.

Katie Taylor

December 29, 2025If you’re over 65 and tired? Go get an echo TODAY. Don’t wait for your doctor to ‘think it’s important.’ Be your own advocate. I did. My dad waited until he passed out. Now he’s alive because I pushed. You can too. Your life is worth fighting for.

Payson Mattes

December 30, 2025Wait… so you’re telling me they’re putting valves in through the GROIN? That’s how they inject vaccines, right? I think this is all part of the Great Cardiac Control Initiative. They want us dependent on devices so they can track our heart rhythms and tie it to the national ID system. Also, pig tissue? That’s a biochip. I read a guy on 4chan who said the FDA is owned by Big Swine.

Isaac Bonillo Alcaina

December 31, 2025You’re all missing the point. The real issue isn’t the valves-it’s the systemic failure of preventive cardiology. If people ate real food, exercised, and stopped taking statins like candy, none of this would be necessary. But no, we’d rather patch a broken system than fix the cause. Pathetic.

Bartholomew Henry Allen

January 1, 2026Transcatheter interventions represent a paradigm shift in structural heart disease management. The data supporting reduced mortality and improved functional status are robust. However, long-term durability remains an area requiring continued surveillance. Institutional volume correlates strongly with procedural success. Patient selection must be multidisciplinary and evidence-based.

Jeffrey Frye

January 1, 2026so i had a murmur since i was 12 and everyone said 'oh its nothing' well guess what my mitral valve is now so stretched out they had to replace it. and yeah the recovery sucked but i can actually breathe now. also i think the word is 'regurgitation' not 'regurgatation' lol

Chris Buchanan

January 1, 2026Listen. If you’ve ever felt winded climbing one flight of stairs and thought ‘I’m just getting old’-you’re lying to yourself. That’s not aging. That’s your heart screaming. I’ve seen it. My neighbor, 71, thought he was just out of shape. Got an echo. Severe aortic stenosis. TAVR. Two weeks later he was hiking with his dog. You don’t need to suffer. Get checked. Now.

Wilton Holliday

January 3, 2026Just had my dad get MitraClip last month. He’s 78, had COPD, thought he’d never feel normal again. Now he’s laughing again. Took him 3 weeks. Not a miracle, but close. <3

And hey-if you’re reading this and scared? I get it. But the scariest thing isn’t the procedure. It’s waiting. You’ve got this. And you’re not alone.