2 Dec 2025

- 15 Comments

Medication Disposal Guide

Select Your Scenario

Every year, millions of unused or expired pills sit in bathroom cabinets, kitchen drawers, and medicine chests across the U.S. Most people don’t know what to do with them-so they keep them, toss them in the trash, or worse, flush them down the toilet. But improper disposal isn’t just sloppy-it’s dangerous. Unused opioids alone contributed to over 13,000 overdose deaths in 2022. The FDA medication take-back system was built to stop that.

What the FDA Says About Disposing of Medications

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has clear, science-backed rules for getting rid of old medicines. Their message is simple: take-back is always the best option. In 2024, the FDA updated its guidelines to make this even clearer. Out of all the medications dispensed in the U.S. each year, about 15-20% go unused. That’s billions of pills. If even a small fraction ends up in the wrong hands or in waterways, the risks add up fast.The FDA’s top recommendation? Use a drug take-back location. These are drop-off spots-usually at pharmacies, hospitals, or police stations-where you can safely hand over old meds. No questions asked. No cost. No risk. In 2025, there are over 14,352 DEA-authorized take-back locations across the country. That’s more than one in every two U.S. counties has at least one.

When You Can’t Use a Take-Back Program

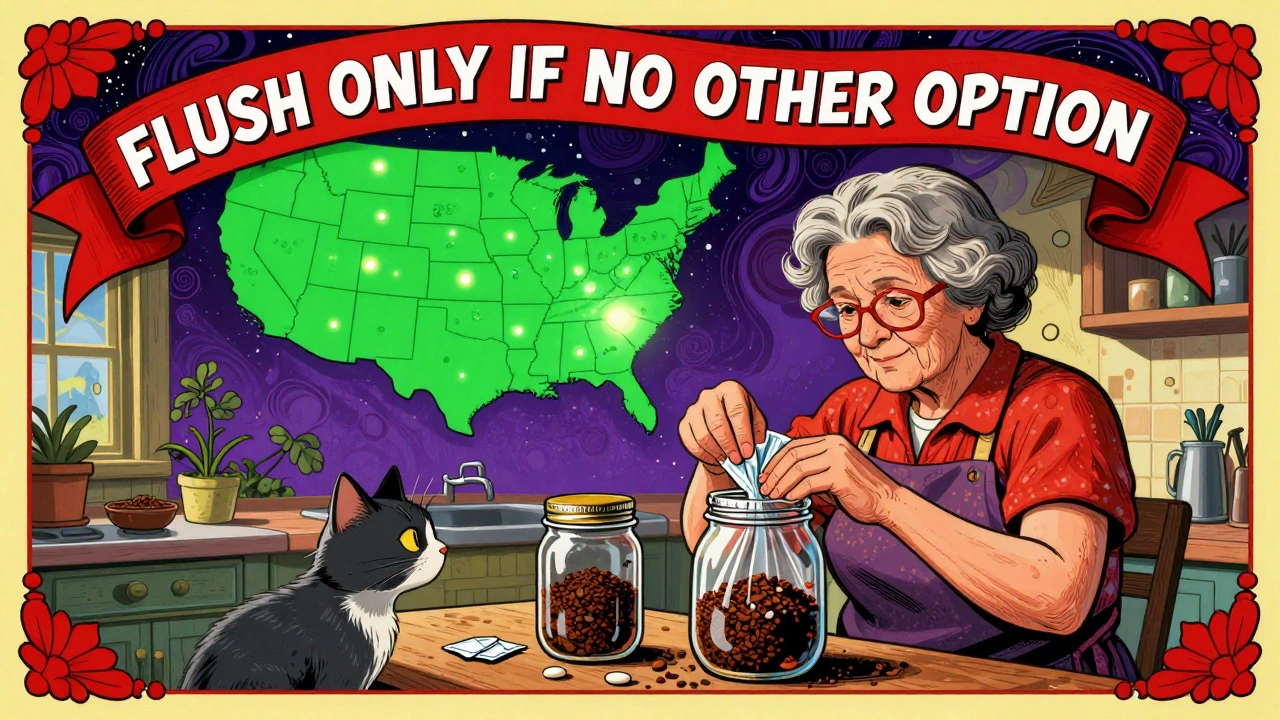

Not everyone lives near a drop-off site. Rural areas, in particular, face real barriers. The FDA defines “readily available” as a location within 15 miles or a 30-minute drive. If you’re outside that range, you have two other options: mail-back envelopes or home disposal. But here’s the catch: only one type of medication should ever be flushed.The FDA maintains a Flush List-a short list of 13 high-risk medications that can be flushed only if no take-back option exists. These include powerful opioids like fentanyl, oxycodone, and hydrocodone, plus a few others like buprenorphine (added in the 2024 update). Why flush these? Because if they fall into the wrong hands-especially kids or people with addiction-they can be deadly. Flushing removes them from the home immediately.

But here’s the twist: the EPA disagrees. The Environmental Protection Agency says flushing should never be the first choice, even for these drugs, because trace amounts can end up in rivers and lakes. The FDA acknowledges this, but says safety from overdose comes first. So if you have fentanyl patches or unused oxycodone and no take-back nearby? Flush them. Otherwise? Don’t.

How to Dispose of Non-Flush List Medications at Home

If your meds aren’t on the Flush List-and you can’t get to a take-back site-here’s the only safe way to throw them away:- Remove personal info. Scratch out your name, prescription number, and pharmacy details with a permanent marker. Or use an alcohol swab to wipe it off. Don’t just peel the label-do it right.

- Mix with something unpalatable. Take the pills (or crush them if they’re not extended-release) and mix them with an equal amount of something gross-like used coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt. The FDA says this makes them unappealing and hard to misuse.

- Seal it tight. Put the mixture into a sealed plastic container. The FDA recommends plastic at least 0.5mm thick. Ziplock bags are fine, but double-bagging is better.

- Throw it in the trash. Not the recycling bin. Not the compost. Just the regular garbage.

- Recycle the empty bottle. Once you’ve scrubbed off all personal info, you can recycle the bottle. Most curbside programs accept plastic prescription bottles.

People mess this up all the time. In a 2023 FDA study, 12.7% of home disposal attempts failed. The biggest mistakes? Not mixing the meds with enough absorbent material (43.8% of failures) or using flimsy containers that leak (37.2%). One Reddit user, a hospital pharmacist with 12 years of experience, said: “I see patients throw liquid meds straight in the trash. That’s a disaster waiting to happen. They have to be mixed with coffee grounds or kitty litter first.”

Mail-Back Envelopes: A Convenient Alternative

If you hate driving to a drop-off or don’t trust yourself to mix meds properly, mail-back programs are a solid middle ground. Companies like DisposeRx and Sharps Compliance provide pre-paid envelopes that you fill with your old pills, seal, and drop in the mailbox. The DEA and FDA both approve these systems, and they meet strict postal standards (USPS Domestic Mail Manual Section 604.8.0).They’re not free-costing between $2.15 and $4.75 per envelope-but many insurance plans and pharmacies offer them for free. Express Scripts, for example, gives them out to 10 million customers a year. In their 2024 survey, 94.2% of users said they’d use it again. Military veterans using VA-provided envelopes showed 89.2% compliance-far higher than the 62.7% who followed standard home disposal rules.

Take-Back Programs Are Working-But Nobody Knows About Them

Here’s the real problem: most people don’t know take-back programs exist. A 2024 survey by a major pharmacy chain found that 63% of patients had never heard of their own in-store drop-off kiosk. Walmart and CVS now have take-back bins in nearly every U.S. location-over 4,700 and counting. Yet, only 35.7% of Americans actually use them.That’s changing. The DEA is expanding the network to 20,000 locations by 2026. The FDA wants 90% of people to use take-back by 2030. And the EPA just announced a $37.5 million grant program to help towns build more collection sites.

But awareness is still low. On Reddit, users say they’ve seen kiosks filled with pills but never seen anyone use them. “I’ve walked past mine for years,” one person wrote. “I didn’t realize I could just drop off my old painkillers like I was returning a book.”

What You Should Never Do

Don’t flush meds unless they’re on the FDA’s Flush List. Even then, only if no other option is close.Don’t pour pills down the sink. Don’t dump liquid meds in the trash without mixing them. Don’t leave them in a bottle with your name on it. Don’t assume “it’s just one pill” doesn’t matter.

And never share your meds-even with family. A 2024 study found that communities with three or more take-back locations per 100,000 people saw an 11.2% drop in teen opioid misuse. That’s because fewer pills were lying around.

What’s New in 2025

The Flush List was updated in October 2024: oxymorphone was removed, and buprenorphine was added. Why? Because buprenorphine is now widely prescribed for opioid addiction-and it’s still dangerous if misused. The DEA also just approved new rules allowing more pharmacies, fire stations, and even some grocery stores to host permanent collection bins.The next National Prescription Drug Take-Back Day is on April 26, 2025. But you don’t have to wait. Permanent sites are open year-round. Just check DEA.gov/takebackday for locations near you.

Final Checklist: Safe Disposal in 5 Steps

- ✅ Check if your medication is on the FDA Flush List (fentanyl, oxycodone, hydrocodone, buprenorphine, etc.)

- ✅ If yes, and a take-back site is within 15 miles? Use it. If not? Flush it.

- ✅ If no, and a take-back site is available? Use it. Period.

- ✅ If no take-back and not on the Flush List? Mix with coffee grounds or cat litter, seal in a plastic bag, throw in trash.

- ✅ Always remove personal info from the bottle before recycling.

It takes less than five minutes. And it might save a life.

Can I flush all expired pills down the toilet?

No. Only the 13 medications on the FDA’s Flush List should ever be flushed-and only if no take-back option is available within 15 miles. Flushing other medications can pollute water supplies and is against EPA guidelines. Most common pills like ibuprofen, antibiotics, or blood pressure meds should never be flushed.

Where can I find a drug take-back location near me?

Go to DEA.gov/takebackday and use their locator tool. Most major pharmacy chains like CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart have permanent drop-off bins in their pharmacies. Police stations, hospitals, and some city halls also host collection sites. As of 2025, over 14,352 locations are active across the U.S.

What if I have liquid medications or insulin?

For liquid medications, pour them into a sealable container and mix with an equal amount of cat litter, coffee grounds, or dirt. Don’t pour them down the drain. For insulin pens or syringes, keep them in their original container and take them to a pharmacy that accepts sharps. Never put loose needles in the trash.

Can I just throw away pills in their original bottle?

No. If you throw away pills in their original bottle, someone could find them and misuse them. Always remove or destroy all personal information first. Even better-take the pills out, mix them with an unpalatable substance, and throw the mixture in the trash. Then recycle the empty bottle after scrubbing off labels.

Is it safe to recycle prescription bottles?

Yes, but only after you’ve completely removed all personal information. Use a permanent marker to black out your name, prescription number, and pharmacy details. Then wipe the bottle with alcohol if possible. Once de-identified, most curbside recycling programs accept #1 or #2 plastic bottles. Don’t recycle them with pills still inside.

Do I need to bring my ID to drop off meds?

No. Take-back programs are anonymous. You don’t need to show ID, explain why you’re dropping off meds, or sign anything. The bins are designed for privacy and safety. Just drop the pills in and leave.

Kevin Estrada

December 4, 2025so i just threw my ex's oxy in the toilet last week and now i feel like a villain?? 😅 like... she was gonna sell them anyway. but now i'm the monster?? 🤡

Katey Korzenietz

December 5, 2025Flushing?! Are you KIDDING me?? This is why our rivers smell like sadness and pharmaceuticals. The EPA is right, the FDA is just being lazy. #SaveTheWater

Ethan McIvor

December 6, 2025it's wild how we treat medicine like trash when it's literally life or death... i mean, we wouldn't just toss a loaded gun in the drawer, but we'll leave fentanyl patches next to the toothpaste? 🤔

Mindy Bilotta

December 6, 2025just did this yesterday! mixed my mom's blood pressure pills with coffee grounds, sealed in a ziplock, tossed it. felt like a responsible adult for once 😌

Michael Bene

December 7, 2025so the FDA says flush these 13 drugs but the EPA says nooo? who do we even trust anymore? the government? lol. i'm just gonna hide mine under the floorboards. someone else can deal with it in 20 years. 🙃

Brian Perry

December 7, 2025i used to flush everything. then my cousin OD'd on some old pills she found in her grandma's cabinet. now i mix everything with kitty litter. it's gross. but so is death.

Chris Jahmil Ignacio

December 8, 2025this is all a psyop. the government wants you to think you're doing the right thing by using take-back bins. but what if they're just collecting data? what if they're tracking who's hoarding opioids? what if they're building a database for future control? they've been doing this since the 1970s. don't be fooled.

Paul Corcoran

December 9, 2025if you're reading this and you've been holding onto old meds because you 'might need them' - please stop. you won't. someone else might. and that someone else might not survive. take the five minutes. it matters.

Colin Mitchell

December 10, 2025just dropped off my dad's painkillers at the CVS down the street. the lady behind the counter smiled and said 'thank you for doing the right thing.' felt good. small acts, big impact.

Stacy Natanielle

December 11, 2025The FDA’s Flush List is a statistically significant outlier in public health policy. The EPA’s environmental impact assessment, published in 2023, demonstrates a 0.004% concentration increase in aquatic ecosystems from flushable opioids. However, the risk-benefit ratio is skewed by sociocultural factors related to domestic access control. In other words: you’re not saving lives-you’re just avoiding liability.

kelly mckeown

December 13, 2025i never knew you could recycle the bottles... i always just tossed them. thanks for that. also, i'm gonna go mix my expired zoloft with coffee grounds tonight. i feel like i'm finally doing something right.

Tom Costello

December 14, 2025took my pills to the fire station last week. they had a bin right by the entrance. no one was there. i just dropped them in. felt like i was putting a letter in the mail. simple. quiet. done.

dylan dowsett

December 16, 2025Wait-so you’re telling me I can’t just toss my antibiotics in the trash?!!?!?!?!?!?!? That’s ridiculous. I’ve been doing it for years. What’s the worst that could happen? A raccoon gets sick? Big deal.

Susan Haboustak

December 17, 2025This entire guide is a distraction. The real problem is pharmaceutical companies overprescribing. Stop blaming the consumer. They’re just trying to survive. And now you want them to jump through hoops? How about holding the manufacturers accountable?

Chad Kennedy

December 17, 2025i just threw my whole medicine cabinet in the trash. who cares? it's not like anyone's gonna dig through my garbage. and if they do? good luck.