13 Feb 2026

- 12 Comments

Protein-Medication Timing Calculator

Protein intake timing can significantly affect how well your medication works. This tool helps you calculate how much protein to consume at each meal to maximize drug absorption and minimize symptom flare-ups.

Your Protein Schedule

Recommended Distribution

For Parkinson's patients taking levodopa, the protein-redistribution diet can add up to 2.5 hours of symptom-free time per day. Most protein should be consumed in the evening.

When taking protein-sensitive medications, aim to consume 30g or less of protein before medication and 70% or more at dinner.

Protein intake timing is critical for medications like levodopa. Taking protein-rich foods 30-60 minutes after medication can reduce effectiveness by 30-50%.

When you take a pill, you expect it to work. But what you eat right before or after that pill can make a big difference-sometimes even stopping it from working at all. This isn’t just a myth or old wives’ tale. For people taking certain medications, especially for conditions like Parkinson’s disease, the protein in their meals can directly interfere with how well the drug gets into the bloodstream and reaches its target. The science behind this is clear, well-documented, and often overlooked by both patients and doctors.

How Protein Blocks Medication Absorption

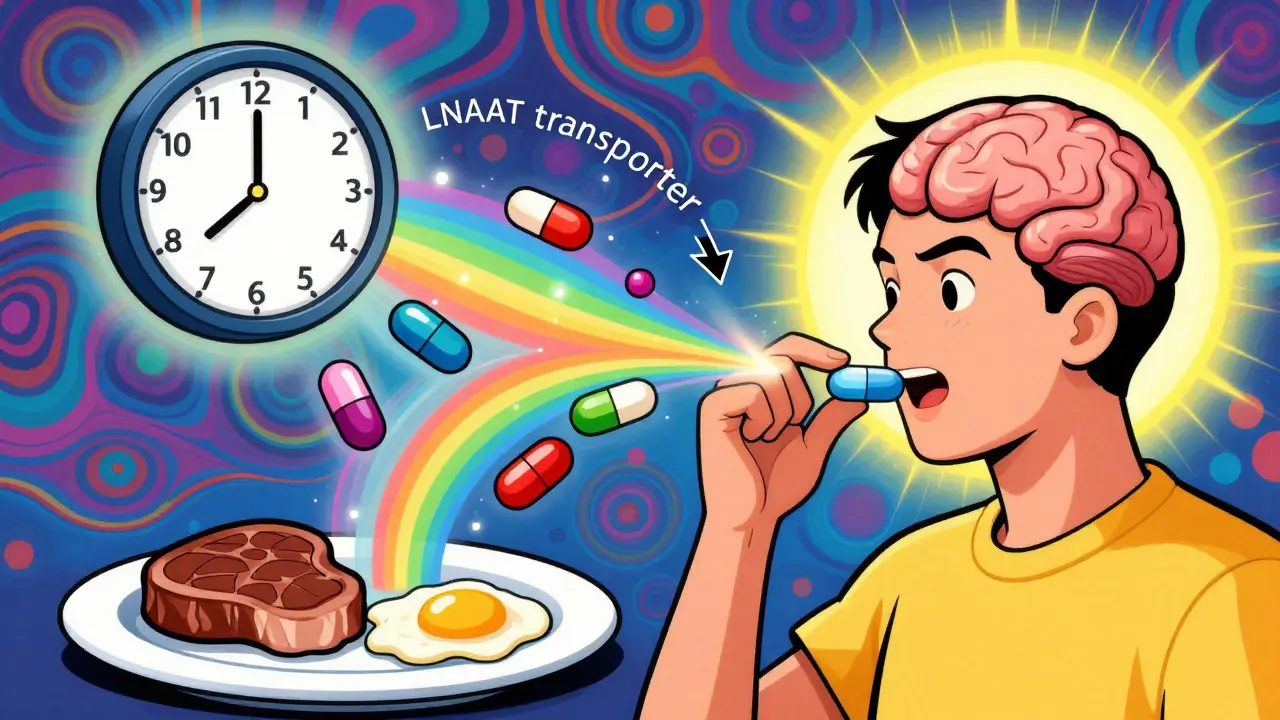

The body doesn’t treat all nutrients the same way when it comes to absorbing drugs. Protein-rich foods break down into amino acids, and those amino acids compete with certain medications for the same transport system in the gut and blood-brain barrier. This system, called the large neutral amino acid transporter (LNAAT), is designed to carry essential amino acids like leucine, isoleucine, and valine into the bloodstream and brain. But it also carries drugs like levodopa-the main treatment for Parkinson’s disease.

When you eat a steak, a bowl of lentils, or even a protein shake, your blood levels of amino acids spike within 30 minutes. That flood of amino acids overwhelms the transporters. Levodopa, which needs those same pathways to enter the brain, gets pushed out of the way. Studies show this can reduce levodopa absorption by 30% to 50% in about 60% of patients. That means less drug reaches the brain, and symptoms like stiffness, tremors, and slowness come back sooner.

This isn’t unique to levodopa. Other drugs that rely on these transporters include certain antiepileptic medications and some antibiotics. The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) puts drugs like levodopa in Class III: high solubility, low permeability. These are the ones most likely to be affected by food. In contrast, drugs that easily pass through cell membranes (Class I) like some cholesterol medications show little to no change with protein intake.

Not All Protein Is Equal-Timing Matters More Than You Think

It’s not about cutting out protein entirely. The body needs protein to maintain muscle, repair tissue, and support immune function. The problem is timing. Eating a high-protein breakfast or lunch right before taking levodopa can sabotage the whole day’s symptom control.

Research from the Michael J. Fox Foundation and Parkinson’s Canada shows that shifting most of your daily protein to the evening meal can dramatically improve daytime function. This is called the protein-redistribution diet. Instead of spreading protein evenly across three meals, you eat only 30 grams at breakfast and lunch, and save 70 grams for dinner. One study found this simple switch added 2.5 hours of good symptom control per day-time when patients could walk, talk, and move without freezing or shaking.

For many, this means swapping a scrambled egg and bacon breakfast for oatmeal with fruit. A turkey sandwich at lunch becomes a salad with beans and veggies. At dinner, the steak returns. It’s not about deprivation-it’s about rearranging.

Doctors at the University of Cincinnati and Duke University point out that 68% of clinicians never discuss this with patients starting levodopa. That’s a gap that leads to unnecessary suffering. Patients aren’t being told the truth: your medicine might be working fine, but your lunch is blocking it.

What About Other Medications?

Levodopa is the most studied, but it’s not the only one. Antibiotics like penicillin and amoxicillin can also be affected. High-protein meals delay gastric emptying by 45 to 60 minutes, which changes when the drug hits the small intestine where absorption happens. This can lower peak blood levels by 15% to 20%, reducing how well the antibiotic fights infection.

On the flip side, some drugs actually absorb better with protein. Certain antibiotics, especially those that are poorly soluble, benefit from the increased blood flow and bile secretion triggered by a protein-rich meal. But these cases are rare. Most of the time, protein is a problem, not a helper.

Even supplements can be affected. Iron pills, often taken for anemia, compete with amino acids for absorption. Taking them with a protein shake can cut iron uptake by up to 40%. Same goes for zinc and calcium supplements.

Real People, Real Results

Online forums are full of stories. On the Parkinson’s Foundation Forum, 68% of users say taking their medication 45 minutes before eating made a noticeable difference. One Reddit user, u/ParkinsonsWarrior, tracked their symptoms with a wearable sensor and found that after switching to protein redistribution, their daily ‘off’ time dropped from over five hours to just over two. That’s a life-changing shift.

But there are downsides. Some people who tried strict low-protein diets ended up losing muscle mass. A 2024 study in the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease found 23% of patients on very low-protein diets developed muscle wasting within 18 months. That’s why experts don’t recommend cutting protein-they recommend moving it.

Another user, u/TremblingHands, tried the low-protein route and lost 15 pounds. Switching to Duopa-a gel delivered directly into the small intestine-helped them regain 8 pounds in three months. That’s because Duopa bypasses the stomach and gut entirely, avoiding the protein competition problem.

Practical Tips for Managing Protein and Medication

If you’re on a medication that might interact with protein, here’s what works:

- Take meds 30 to 60 minutes before meals. This gives the drug time to absorb before protein hits your system. Avoid eating protein-rich foods during this window.

- Use low-protein snacks if needed. If nausea strikes, choose snacks under 5g of protein: fruit, rice cakes, or a slice of low-protein bread (some brands now offer versions with just 2g per slice).

- Shift protein to dinner. Aim for 70% of your daily protein at night. That keeps daytime drug absorption clear.

- Track your intake. Apps like ProteinTracker for PD help monitor daily protein. Users report 40% fewer timing mistakes after using them.

- Ask about alternatives. If timing doesn’t help, talk to your doctor about formulations that bypass the gut-like Duopa, or injectable options.

Even small changes matter. A granola bar with 7g of protein might seem healthy, but if taken with your morning pill, it could be enough to trigger a bad day of symptoms.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The medical world is finally catching up. The FDA now requires all new drugs to be tested with both low- and high-protein meals. Since 2022, 78% of major drug companies use the Biopharmaceutics Drug Disposition Classification System (BDDCS) to flag protein-sensitive medications. The European Medicines Agency now requires protein-specific warnings on labels for all CNS drugs.

And new tools are emerging. A 2025 study from Nature Medicine showed that certain probiotics could reduce protein competition for drug transporters by 25%. Time-restricted eating-consuming all protein between noon and 8 p.m.-improved levodopa effectiveness by 32% in 78% of participants. The FDA is even drafting a new label format: a “Protein Interaction Score,” similar to alcohol warnings on bottles.

By 2030, personalized algorithms that adjust medication timing based on daily protein intake could cut therapeutic failures by 45%. That’s not science fiction-it’s happening in labs at Massachusetts General Hospital right now.

Don’t Guess. Get Help.

This isn’t something you figure out alone. Working with a dietitian who specializes in Parkinson’s or neurology can make all the difference. Most patients struggle at first, but 78% achieve better control after just three sessions. The key is not to stop eating protein. It’s to eat it at the right time.

If you’re on medication and notice your symptoms getting worse after meals, ask your doctor: Could protein be affecting how this drug works? You might be surprised by the answer-and relieved by the fix.

Can eating protein with my medication make it completely ineffective?

For some medications like levodopa, protein can reduce absorption by up to 50%, which means the drug may not work well enough to control symptoms. It doesn’t make the drug completely useless, but it can cut its effectiveness in half, leading to sudden worsening of symptoms like tremors or stiffness.

Should I stop eating protein if I’m on medication?

No. Protein is essential for muscle, immune function, and overall health. Cutting it too much can lead to muscle loss, weakness, and malnutrition. Instead, shift most of your protein to your evening meal and take your medication 30-60 minutes before breakfast and lunch.

Which medications are most affected by protein?

Levodopa (for Parkinson’s) is the most well-known. Others include carbidopa-levodopa combinations, certain antibiotics like penicillin and amoxicillin, and some antiepileptic drugs. Iron, zinc, and calcium supplements can also be less effective when taken with high-protein meals.

How long before a meal should I take my medication?

For drugs affected by protein, take them 30 to 60 minutes before eating. This gives the medication time to be absorbed before protein from your meal starts competing for the same transporters in your gut.

Are there any foods I should avoid completely?

You don’t need to avoid any foods entirely. But avoid high-protein foods-meat, dairy, eggs, beans, soy, and protein shakes-within an hour of taking your medication. Low-protein snacks like fruit, rice cakes, or plain oatmeal are safe.

Can I use apps to track my protein intake?

Yes. Apps like ProteinTracker for PD were developed specifically for people on levodopa. They help you log daily protein and remind you when to take medication. Users report 40% fewer timing errors and better symptom control after using them.

What if I’m dining out and can’t control what I eat?

Dining out is a common challenge. Ask for meals with less protein-grilled vegetables, rice, or pasta without meat. If you can’t avoid protein, try taking your medication a little earlier, or ask your doctor about alternatives like Duopa, which bypasses the digestive system entirely.

Is this issue only for Parkinson’s patients?

No. While Parkinson’s is the most studied, other conditions like epilepsy, chronic infections, and even some mental health medications can be affected. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist or doctor whether your medication has known food interactions.

How do I know if my medication is affected by protein?

Check the medication guide. If it mentions food interactions, especially with high-protein meals, it’s likely affected. If you notice your symptoms worsen after meals, that’s another clue. Talk to your doctor-they can check the drug’s classification (BCS Class III) or run a simple test to see if absorption improves when you take it on an empty stomach.

Can protein interactions cause long-term damage?

Not directly. But if your medication doesn’t work well for months or years because of protein interference, your condition can worsen. For Parkinson’s, that means more falls, more hospital visits, and faster decline. Fixing the timing can prevent this-and save money on avoidable care.

Brad Ralph

February 14, 2026So basically, my steak breakfast is sabotaging my Parkinson’s meds? 🤡 I’ve been eating eggs and bacon for 12 years and now I’m told to switch to oatmeal? I’ll take my levodopa with a side of existential dread.

christian jon

February 14, 2026THIS IS A SCAM! The pharmaceutical-industrial complex is hiding the TRUTH! Protein isn’t the enemy-GLYCEMIC INDEX IS! They don’t want you to know that insulin spikes from CARBS are what’s REALLY blocking absorption! And don’t get me started on the GMO soy in those ‘low-protein’ rice cakes! It’s all a cover-up for Big Pharma’s profit margins! 🚨

Suzette Smith

February 16, 2026I tried the protein redistribution thing for a week and ended up eating spaghetti with marinara for dinner every night. My husband said I looked like a 1950s TV mom. But my tremors? Gone. So… worth it?

Autumn Frankart

February 18, 2026You think this is about protein? Nah. It’s the glyphosate. They spike the food with it to make meds less effective so people need MORE meds. And the ‘protein redistribution’? That’s just a distraction. The real fix is chelation therapy and grounding your feet on the earth every morning. I’ve been doing it for 3 years. My levodopa dose? Cut in half. The FDA won’t tell you this because they’re owned by Monsanto.

Pat Mun

February 18, 2026I’ve been managing Parkinson’s for 8 years, and this article finally made me feel seen. The protein timing shift? Game-changer. I started eating my chicken and beans at 7 p.m. and now I can dance with my granddaughter without freezing. I used to cry after dinner because I couldn’t hold her hand. Now? We waltz in the kitchen. It’s not magic-it’s science. And yes, I cried again. But this time, it was joy. If you’re struggling, please don’t give up. You’re not broken. You’re just timing it wrong.

andres az

February 20, 2026BCS Class III drugs are inherently bioavailability-limited due to low permeability. The LNAAT competition is a well-documented pharmacokinetic phenomenon. The ‘protein redistribution diet’ is just a heuristic workaround for suboptimal drug design. We should be developing prodrugs that bypass the transporter entirely. Why are we optimizing meal schedules instead of fixing the pharmacology?

Steve DESTIVELLE

February 22, 2026In the grand cycle of existence, protein is merely energy in motion. The body does not distinguish between steak and pill. The mind creates separation. When you eat, you are not consuming food. You are becoming the universe. The levodopa is already in your brain. The meal is just a mirror. Your suffering comes not from protein, but from the illusion that you are separate from the medicine. Let go. Breathe. Let the amino acids flow.

Stephon Devereux

February 23, 2026I’m a neurology pharmacist and I can’t tell you how many patients I’ve seen who think they’re ‘failing’ at treatment-when really, their lunch is just outcompeting their drug. The protein redistribution diet works because it’s not about restriction-it’s about strategy. I tell my patients: ‘Think of your gut like a highway. Protein is rush hour. Your drug is a lone car trying to get through. Move your protein to nighttime, and suddenly, your drug gets the express lane.’ Simple. Effective. Underrated.

Craig Staszak

February 24, 2026I’ve been on levodopa for 15 years and never knew this. Took me 3 days to shift my protein to dinner. Now I can tie my shoes without help. No drama. No supplements. Just timing. Why isn’t this on every prescription bottle?

Reggie McIntyre

February 25, 2026I used to think I was just getting worse as I aged. Turns out, my 7 a.m. protein shake was blocking my meds. Switched to fruit and a slice of low-protein bread-boom. Two extra hours of mobility. I’m not a scientist, but I know this: if your meds feel less effective after meals, it’s not you. It’s the timing. Try it. Your future self will high-five you.

Carla McKinney

February 25, 2026Let’s be real. The ‘protein redistribution diet’ is just a band-aid. The real issue is that levodopa is a 60-year-old drug with terrible pharmacokinetics. We’re patching a sinking ship with duct tape while the FDA approves new drugs that cost $120,000/year. This isn’t healthcare. It’s triage for the underinsured. And now we’re telling people to eat oatmeal? How noble. How tragic.

Ojus Save

February 26, 2026i did the protein shift and it workd but now i cant sleep cause my body is too full at night lol. also my wife says i smell like lentils. but i can walk so... worth it?